Liftoff for India’s Private Space Sector

In 2014, India became the fourth nation to reach Mars as the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO; the Indian equivalent of NASA) successfully put its space probe Mangalyaan into the red planet’s orbit. What’s more, they did it with a budget of only 17 million USD. To put that cost into perspective, the blockbuster film The Martian, released only a year later, had a production budget of 108 million USD. For over 50 years, India has consistently invested in its space infrastructure, making ISRO one of the top and most efficient national space programs globally with a track record of accomplishments to show for it. Still, there is no Indian SpaceX or Virgin Galactic. India’s private space agency has long had few if any, superstars.

By all the numbers, these last few years should have seen India become a force to be reckoned with in the space sector. Its Technology Readiness Level is higher in the space sector than in aviation. Investment as a percentage of GDP is 30% higher in India than the world median and 45% greater than that of the United States. Over 500 Indian companies supply ISRO with space equipment. But with 17% of the world’s population and bustling academic and technological circles, the country only commands 2% of the world’s private space industry. What went wrong?

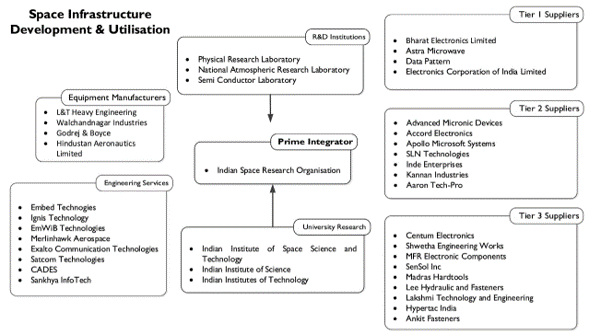

For years, India has actively promoted its private space industry. In a video as a part of the Make in India campaign, ISRO attributes their cost-effectiveness to their practice of outsourcing design and components. These contracts were specifically targeted at small and medium enterprises and used to promote the Indian space economy. However, this growth could only legally occur in ISRO's shadow. Per Indian policy, firms operating in the space sector could only do so as a subcontractor to the ISRO. Legally, firms were not allowed to make it out on their own. As the diagram below illustrates, the Indian space industry was highly centralized, with all value chains flowing to ISRO.

Provided by Nagendra and Basu, (2016). Demystifying space business in India and issues for the development of a globally competitive private space industry. Space Policy, 36, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2016.02.006

The ISRO’s three commissioned launchpads were also off the table to private space companies, reserved only for ISRO rockets. And neither could companies build their own launchpads, as monumental of a task that would be. With no integrated value chain and wholly subservient to ISRO projects, the Indian companies have not been able to make it on their own and burst into the limelight.

Industry leaders are hoping that is all about to change. As a part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Self Reliant India (Aatmanirbhar Bharat) campaign, India released its Spacecom Policy 2020 in November 2020. The document outlines radical changes to the Indian space industry. Spacecom Policy 2020 allows private companies access to the ISRO’s launchpads, Satcom capacity, and in essence, the entire ecosystem of the ISRO for support. Space companies no longer have to operate under the wing of the ISRO; they can develop, launch, and profit off of their own spacecraft. This liberation of private space companies was preceded by the June announcement of a new agency, IN-SPACe, devoted to facilitating public-private cooperation, identifying the private sector’s needs, and promoting an industry-led space economy for India.

If industry’s self-reliance is the goal, India’s commercial space industry is well-posed for it. In addition to an impressively built infrastructure, over 200 of the nation’s engineering colleges teach aeronautical engineering. In India, private companies are already priming their engines, with one company, Skyroot, already set for liftoff.

Skyroot founders Naga Bharath Daka (right) and Pawan Kumar (left).

Together with a cadre of other ISRO scientists, Pawan Kumar Chandana and Naga Bharath Daka founded Skyroot in 2018. The company has already raised 4.3 million USD in funding and expects another 15 million in 2021. The company is developing a family of space rockets crafted to service the small satellite market.

Most recently, Skyroot made headlines after receiving the green light to use ISRO launchpads for their Vikram-1 launch vehicle, named after the father of India’s space program Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai. This follows the announcement last summer that Skyroot had successfully test-fired its first solid propulsion rocket Kalam-5.

It’s a new day for space in India, now with private companies set to lead the way. Indian space is open for business. With luck, perhaps India’s next trip to Mars will not just stay in orbit.

Connor Brennan is a Junior in Georgetown's School of Foreign Service studying International Political Economy and Mathematics. He is interested in space as an emerging liberalized market and how private development can spur technological development. Connor looks forward to studying the growing space industry and observing how the decisions of industry leaders today will shape the norms of tomorrow.